The Living Word is the fifth and final volume of Inner Land. In contrast to previous volumes, it is not subdivided into chapters. If readers find it less coherent or conclusive than previous chapters, this may be because Arnold was still working on it up until his death, and never completed the manuscript to his satisfaction. His eldest son Eberhard C. H. Arnold (“Hardy”) drew on his father’s notes and talks, as well as the 1918/23 edition of Inner Land, to complete the book.

This volume also includes extensive expositions on three sixteenth-century figures, all noted for their radical views on the word of God. It is easy to get lost in the outlines of Hans Denck’s, Sebastian Franck’s, and Thomas Müntzer’s thought, confusing these with Arnold’s own arguments. But Arnold does not want to commend every claim of each figure. Rather, he provides overviews in order to share what is valuable about their witness, as well as to identify what might detract from it, especially in comparison to other thinkers in what would later become the Hutterite stream of Anabaptism. This article will help clarify Arnold’s views in that connection.

Arnold introduces the volume with a reflection on the need for clarity in order to fulfill our calling. We can seek clarity within, which is necessary, but without God’s voice we only have our own voices, and these are tainted by our sinful nature. True clarity comes from Jesus Christ alone, the living word.

This theme of “living word” or “inner word,” which is the focus of the volume, is part of a tradition that goes back to the Radical Reformation in the sixteenth century and has roots in earlier expressions of Christian spirituality as well.1 It is somewhat related to the figure of the Word in the Bible, most famously expressed in John’s Gospel: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God” (1:1). In Christ, “The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us” (1:14). But when Arnold and those he cites mention the inner word, they are generally not referring to the eternal Word and its historical manifestation in Christ but specifically to the voice of God within individual believers, sometimes identified with the presence of Christ or the Holy Spirit. This inner word is also consistently contrasted with the outer word, that is, preaching, scripture, and whatever other external means for expressing truths about God and the gospel.

Following this brief comment on the need for clarity, Arnold proceeds to the first of a number of sixteenth-century figures whose contributions he will reflect on throughout the volume. He begins with Ulrich Stadler, who writes of the necessity of receiving the word in a Trinitarian manner.2 As Arnold puts it, “God’s word, like God himself, can also be understood only in the unity that is clearly differentiated in the Father, the Son, and the Spirit” (2). That is, God’s power leads us to recognition of him as Creator and Father, but we also know him in his righteousness in the Son and his kindness in the Spirit. While the first path is open to anyone who reflects on creation, though, the other two paths can only be reached through faith in Christ and the renewing work of the Spirit. Thus, cultivating the living word within means following in Jesus’ footsteps to the cross. It means obedience and action, suffering and poverty. Yet, in the midst of this, we come to know God’s kindness in the presence of the Spirit, who “lives in them [believers] as the living word of eternal truth” (4).

Importantly, this Trinitarian shape of Christian experience, from creatureliness before the Father, to suffering in the Son, to love kindled by the Spirit, enables us to properly understand God’s outer word as it is found in the Bible. Arnold refers to this experience as “the unity of the Trinity” (4), which the Spirit in particular brings about for us – a nod to both the Spirit’s illuminating work and his role in eternally uniting the Father and the Son in classical Christian thought. Thus, “in his light the whole of scripture, with all the words and sayings of God and Christ, is encompassed in the unity of the Trinity. In this unity the scripture speaks of the true, godly life; and in the Spirit we shall see how to achieve it” (4).

The Spirit can guide us in all things, “though it may not be written on the pages of the Bible in front of us” (4), a claim that at the very least reveals the superiority of the inner word to the written, outer word in Arnold’s mind. It also opens the way for making scripture superfluous, however, and Arnold will comment on this problem later on. In the meantime, he can emphasize their basic unity: the inner word “is in perfect accord with every line written by his apostles and prophets, who were filled with the same inner word” (5).

At this point, Arnold identifies the living word with Christ: “The Holy Spirit plants the living word – Christ – into the heart of the believing church” (5). Christ is “the inner word in all believers” (5). These claims recall the figure of the eternal Word in the Gospel of John and other biblical texts, mentioned above. Again, however, Arnold’s focus in this chapter is on Christ’s presence within believers as the ultimate and only true guide, more than his eternal existence from before creation and more than his historical life on earth, however important these are in other contexts. Notably, Arnold also identifies the Spirit with the living word in one place: “The Holy Spirit rejects in them everything of the world. He lives in them as the living word of eternal truth” (4). But this is an anomaly. Throughout the volume, the Spirit is presented not as the word itself but as the one who brings Christ the word into believers’ hearts. As such, Arnold regularly uses terms such as “word of the Spirit” (e.g., 8–10) and “Spirit of (Jesus) Christ” (e.g., 12, 16), among others, to illustrate the differentiated roles of the two divine persons. Nonetheless, “Christ is one with the Spirit” (71), so such distinctions do not need to be held too rigidly when reading Inner Land.3

The conversation with Stadler begins to fade into the background here, and Arnold returns to material from the 1918/23 edition of Inner Land. He reminds his readers that the living word can free us from inner unclarity. Indeed, receiving the word is like seeing a doctor, but “a doctor’s visit can help only when the patient takes the doctor’s words to heart and disregards none of the instructions or medicines” (5). In the same way, we must set aside our own inner counsel and that of others in order to be led by the living word alone. Importantly, this word is not something that we can conjure up within ourselves. We receive it in faith from the Holy Spirit, and this faith can only be given by God.

Drawing on two brief excerpts from another sixteenth-century figure, Peter Riedemann, Arnold reflects on the example of Mary, who provides an analogy for individuals coming to faith. Only after she heard and beleived the message of the angel, Riedemann writes, did the Spirit enable her to conceive. Similarly, we too need to first hear the word in order to find faith and be renewed by the Holy Spirit. Nonetheless, Arnold is wary of taking the word that brings faith and reducing it to something like preaching. He cites Rom. 10:17, “Faith arises from proclamation, but proclamation comes from the word of God” (8). It is not the message itself that brings faith but the living word within it, Christ. This distinction will be made clearer later on.

The renewal that follows hearing the word and receiving it in faith coincides with the Spirit planting the living word within us. It is through this word that the Spirit gives us new life and “produces the works of his love” (8). He does what the law in the old covenant could not do, because it demanded works where there was no life to produce them. Moreover, we are set free from slavery to the law; our works are motivated by love rather than compulsion. This distinction between life under the law and life in the Spirit occasions a comment on the word of God as it appears in the Bible. It is not enough to “only ’open’ the ‘word of God’ and consider it, only hear it and read it, only understand it and think about it, only approve of it and acknowledge it.” We need to “receive it and cherish it in the innermost depths of our hearts as a living seed of God” (10). While he does not state it explicitly, Arnold’s placement of this sentence invites a comparison between obedience to the law without the Spirit and reading scripture without an inner connection to the living word. With the word within us, everything belonging to the old order of sin and death is confronted and pushed out, including works of human origin.

Arnold offers further reflection on the relationship between the Bible and the living word. This word, which we know as Christ, was present before creation, “before the first pages of the Bible were written” (12). Indeed, all things were made through it. It became flesh in the historical Jesus Christ, who revealed who God is. And, “even now, after the last page of the Bible has been written, the word remains the living, creative word” (13). The eternal, living word is superior to the written word of scripture. As Arnold writes a few pages later, “If the whole of scripture were to be put before people’s eyes at once, it would still bring neither fruit nor improvement unless it were done according to the directions of the Spirit who alone knows the truth” (16).

Relatedly, preaching means nothing unless the word is alive within those who preach. As Stadler puts it, those without the word “do not get beyond the shouting of the external sound” (14). Similarly, Riedemann observes that Christ required his disciples to wait upon and receive the Spirit before sharing the gospel – a requirement that should apply to all preachers. In fact, being led by the Spirit extends to every area of a person’s life, including other forms of speech like singing, praying, and conversing, so that these too should be animated by the inner word. Arnold draws a distinction between “the eternal word,” which “is not written by any person, either on paper or on tablets,” and the created words of human beings, which include preaching and even the words of the prophets and apostles in scripture (19). The outer word of creation “presupposes the first and proceeds from the first” because “the direct and living word is always of first importance” (19).4

Arnold’s articulation of the distinction between inner and outer word runs into a difficulty here, however. He wants to say that it is God who makes the outer word effective, and not only in the hearer but the speaker too:

Whoever wants to be a child of the Spirit and a servant of his truth must let the power and works of the Spirit be seen in all his words and above all in his life. Whoever presumes to preach the gospel in any other way is a thief. He offers stolen goods, which in his hands have become worthless. Whoever would run in haste without the power of the Spirit, before Christ has seized hold of him, is a murderer. He brings people to mortal ruin. His word, devoid of the Spirit, is deadly. It reeks of decay, it stuns, it kills life. (17)

But why can’t God work in spite of the preachers who don’t practice what they preach, nonetheless bringing life to those who hear their words? While Arnold does not reject this possibility, it is not in his purview either. The description is suggestive not simply of hypocritical preachers but of false teachers and false prophets – those whose words go beyond denying God in secret to actively seeking to lead their hearers astray. The sixteenth-century context is also important here as Arnold implicitly adopts the criticisms that Anabaptists directed at a Christendom they believed was more interested in worldly gain than service to Christ, and which misused the Bible to justify this. It is likely in this sense that Arnold views the outer word as ineffective without the inner word at work in both hearer and speaker.

In the following pages, Arnold gives further attention to the distinction between outer and inner word, going so far as to warn of the dangers of human words becoming “idols” or “false gods,” even though “they are all nothing but tools or images” (24). Importantly, the New Testament is no different from the Old Testament in this sense, insofar as it requires the inner word to make its witness effective in us. The Anabaptist Hans Denck (1495–1527) even claimed that, as Arnold puts it, “he could understand nothing of the scriptures unless the day, the day itself, the everlasting light were to break in” (25). Denck petitioned God for the faith required to understand the Bible. He even compiled eighty different biblical passages that appeared to variously contradict one other. But with each contradiction, “both passages of scripture must be true, for God’s Spirit deceives no one” (26, quoting Denck). Without the Spirit, human beings are unable to see how these apparent contradictions are in fact united in God’s truth.

The following material is undertaken in further conversation with Denck.5 Arnold briefly comments on the righteousness of God that believers receive through the Spirit. What seems to be a change of topic, though, serves as a segue into additional reflection on God’s truth. The righteous know God and he works through them to the extent that “their word is one with God’s word. … They are able to grasp that the living word in believing hearts is in complete agreement with all the prophets and with all the apostolic scriptures” (28–29). The living word, then, not only brings the Bible to life but ensures the unity of the church in the speech of its members. (Denck’s claim that immediately precedes this discussion, namely that contradictions in scripture are not real but only apparent, would provide the basis for a generous assessment of conflicting claims in different Christian traditions and the possibility of perhaps some of them being reconciled in God’s abundant truth. Arnold does not explore this idea himself, however.)

Next, Arnold offers some more thoughts on the distinction between scripture and the inner word, supported by additional quotes from Denck. Toward the end of this discussion he offers an important qualification: “All this does not mean that for the sake of the living word we should neither listen to sermons nor read the scriptures, for the scriptures testify to the truth” (32). It is simply that the scriptures cannot be rightly understood apart from the inner word. Finally, before Arnold concludes his conversation with Denck, he provides a brief reflection on God’s love, especially as it is expressed in Jesus Christ. It is not clear whether this section is more Arnold’s own thoughts or an exposition of Denck’s. In any case, Arnold wants to underscore here that this love is the center of the Christian life and the definitive characteristic of a person animated by the inner word.

Denck’s theological views bear significant similarities with those of the Hutterites, who formed in the decades following his death. Thus Arnold can write, “Sometimes what Hans Denck says is almost word for word in agreement with the apostolic witness of Peter Riedemann and Ulrich Stadler” (37), both prominent figures in the Hutterite movement. But the Hutterites also developed a more mature theology. In particular, Arnold finds that Denck draws too sharp a distinction between the inner and outer word. The Bible is therefore in danger of becoming superfluous, and the inner word of being confused with the fallen, human conscience. As such, “what is blurred and dimmed in Hans Denck is the true discernment that distinguishes very sharply between the new revelation in Jesus Christ and his Holy Spirit and the work of the deeply corrupted old or first creation” (38).

Arnold proceeds to the work of the historian Sebastian Franck (1499–1543), who had met Denck and some of whose writings were even copied and preserved by Hutterites. Arnold begins by summarizing his approach to the Bible, writing, “For Franck, the holy scriptures are nothing but fantastic and puzzling stories until the Spirit himself, who gave rise to them, expounds the letters” (39). Indeed, those who are knowledgeable in the Bible but lack the Spirit to understand its true meaning often use it as a tool against Christ and his church: “A man whose head is stuffed full of the leaden letters of the Bible, devoid of the Spirit, is as capable of killing the Son of God and his people as the scribes and Pharisees were” (40). Such people are like the scribes and Pharisees in the New Testament, who showed extensive knowledge of the scriptures but “grasped neither their power nor their meaning” (41).

In contrast, the Spirit leads readers to the living truth that the Bible points to and therefore shows scripture to be in accord with itself. This truth is the eternal word, which, hidden for millennia, came to humanity in the flesh in Jesus Christ. The Spirit brings this same word into the hearts of believers, and the truth is no longer hidden from them.

Following this, Arnold offers some reflections on the written word, though it is difficult to determine if he is expounding Franck, expressing his own views, or presenting a combination of both. In any case, the emphasis is on the living truth found in Christ, so that biblical, written accounts necessarily take on secondary importance. Each time the latter are mentioned, the attention is quickly returned to the former. For example: “Now it is a question of understanding Jesus Christ and his whole life in the written history of the Gospels, of grasping Jesus in the records of his spoken word! That means receiving his Spirit into the depths of our hearts! It is a question of living according to this Spirit in the strength of Jesus Christ!” (45–46). It is almost as if Arnold wants to make a statement on the purpose of the Bible, but his intense preoccupation with the Bible’s content, Jesus Christ the living Word (and his Spirit), prevents him from fully carrying this through. Nonetheless, he manages to say that “the written scripture speaks to our hearts in a way we can understand,” and “the word had to be written and has to be proclaimed afresh all the time for the sake of this revelation,” that is, Christ (49). The Bible and preaching are necessary, then, but only insofar as they facilitate the reception of the living word in people’s hearts.

Arnold also considers the nature of preaching in conversation with Franck. Preachers need to wait for the Holy Spirit before they can proclaim the gospel: “When supposedly brilliant preachers obviously contradict themselves or each other, they prove that they have risen before they were awakened” (51). Again, however, no analogy is drawn between the apparent inconsistencies of scripture, which are resolved in God’s greater truth, and the differences in preachers’ claims. Perhaps Franck (or Arnold) has more serious contradictions in mind than those that seem to be present in scripture.

Arnold begins his evaluation of Franck with the observation that he inherited a lot from Denck, and the two historical figures agree in important matters. This also means, however, that Franck runs into similar problems as Denck, so that the emphasis falls more on humanity’s spiritual faculties given at creation and less on the redemptive work of Christ. For example, Franck believed that four hundred years before Christ, Socrates “was, like other pagans, directly spoken to by the living voice and the blowing Spirit of God” (56). Moreover, Franck reads his own tempestuous spiritual journey on to the Christian walk in general so that “the seeker, in anxious fear and need, must be driven to the scriptures, then away from the scriptures, and then back to the scriptures once more” (56). This restlessness finds expression in his theology, which is characterized by the “violent contradictions” he finds in scripture and conflicting claims about God (55).

The final major figure discussed in this chapter is Thomas Müntzer (1489–1525). Like Denck and Franck, the Hutterites would accept what was good in Müntzer’s thought but rejected “the erroneous and impossible alliance between the hammer of the word and the sword of bloody insurrection” (58), a reference to Müntzer’s leading role in the German Peasants’ War. Arnold died before he could complete Inner Land, and what follows was completed by his son, based on Arnold’s talks from October 1933.6

Like Denck and Franck, Müntzer “did not want the word of God to become petrified in the Bible” (58). People needed to hear the living word – a challenge especially to the princes with their worldly comforts – but the authorities would not allow such a word to be preached. Establishment Christianity has other priorities. So Müntzer denounced the “false prophets” who counsel the poor to follow Christ by “let[ting] themselves be worked to the bone by the tyrants” but neglect to “tell the rich and the princes to divest themselves of all their power and riches and humble themselves” (61, quoting Müntzer). No, the call to crucify our desires extends to all who hear the gospel, and only when we put aside power and possession are we free to receive Christ.

The rest of this section is rich with comments on the relationship between scripture and the inner word. The false prophet, for example, “gladly accepts the written word itself, but he will not accept the One who inspired it” (63). Knowledge of the Bible is not a shortcut to knowing Christ; it is only a witness to him, and knowing him requires following him. Nonetheless, because they are a witness, the scriptures “have real importance” (63). Put differently, the Bible “can be a help or a service – therefore it should be read and proclaimed – but it can never itself be the cause of faith” (64). Like Denck and Franck, Müntzer’s critical distinction between the living word of Christ and the functionally dead text of scripture is informed by the actions of the scholars and leaders of the establishment churches in his own time, who used the Bible to validate their ease and comforts at the expense of the populace.

The evaluation of Müntzer repeats the sentiments with which he was introduced: there is much truth in Müntzer, but this is in part undermined by his turn to violence. In the Hutterites, though, who rejected violence, his thought “was further deepened and purified” (69). The paragraphs that follow serve as a more general reflection on the distinction between inner and outer word that constitutes the content of the chapter. The Reformation in Germany – the period comprising Denck, Franck, Müntzer, and the Hutterites – is characterized by two things: “the rediscovery of the Bible in all its breadth and depth, in its integrity and clarity” (69), and the inner word speaking in people’s hearts. This latter feature is the “decisive” one (69). But there is also unity between the two, inner and outer, as the inner allows the outer to be properly understood, and the outer is composed by the prophets and apostles, whose words proceeded from the living word within them.

The remainder of the chapter is mostly made up of material from the 1918/23 edition. Here, the unity between the inner and outer word is described as finding its most authentic expression in our actions. If we are obedient to the voice of the Spirit, our lives will also show clear agreement with the scriptures. Interestingly, this section has a subtly different focus from the rest of the chapter, in which Arnold emphasizes the priority of the inner to the outer word. The demands of the outer word come to the fore as well: “As long as we suppress parts of his scriptures, push them aside, or just refuse to acknowledge them, our inner life will suffer a heavy loss because we withdraw it from the full and undiminished light of the Lord himself” (74). This recalls Arnold’s commitment to nonviolence and community of goods, among other things, on the basis of the New Testament. His contemporaries in other church traditions argued that these were not required of Christians today.7

Inner Land ends with some final reflections on the necessity of the inner word for living the Christian life. This word, Christ, is our essential guide: “It is like the sun suddenly breaking through the fog to show the lost traveler his glorious path – until then he had seen nothing but dark, ghostly shadows” (79).

Continue:

Introduction

1.1. The Inner Life

1.2. The Heart

1.3. Soul and Spirit

2.1. The Conscience and Its Witness

2.2. The Conscience and Its Restoration

3.1. The Experience of God

3.2. The Peace of God

4.1. Light and Fire

4.2. The Holy Spirit

5.1. The Living Word

1. For an overview, see Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online, s. v. “Bible: Inner and Outer Word” (1953), by Wilhelm Wiswedel, https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Bible:_Inner_and_Outer_Word&oldid=91108. The present article follows the capitalization conventions of Plough’s text, even if these sometimes conflict with those used in English Bible translations.

2. This text is elsewhere attributed to Hans Hut and published as “Ein christlicher underricht, wie göttliche geschrift vergleicht und geurtailt solle werden” [A Christian teaching on how divine scripture should be compared and judged], in Lydia Müller, ed., Glaubenszeugnisse oberdeutscher Taufgesinnter [Testimonies of faith from Upper German Anabaptists], 1:28–37 (Heinsius, 1938). Parts of the text have been translated and published in English in Walter Klaassen, ed., Anabaptism in Outline: Selected Primary Sources (Plough, 2019), 74, 89–90, 147.

3. Cf. “God’s word is God’s means of revelation and his creative power. … It is God, for it is God’s Spirit and God’s Son – it is Christ” (12–13).

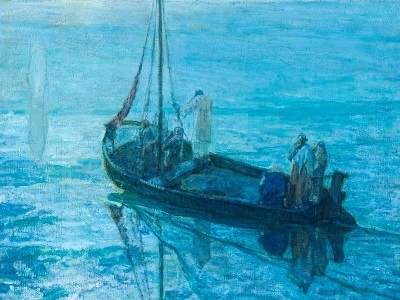

4. Some of Arnold’s argumentation here recalls that of Karl Barth in the first book of his Church Dogmatics, The Doctrine of the Word of God (German 1932). Barth presented the word of God in a hierarchical, threefold form: the word of God preached, that written, and that revealed in Jesus Christ. The preached word depends on the written, and the written on the revealed, yet each is equally the word of God insofar as this hierarchical relationship is maintained. While Arnold shows more interest in sixteenth-century Anabaptist approaches to the word of God, the possibility of an implicit conversation with Barth should not be ruled out, especially given his allusion to Matthias Grünewald’s painting on p. 23 (see n5), a favourite image of Barth’s: “In this connection one might recall John the Baptist in Grünewald's Crucifixion, especially his prodigious index finger. Could anyone point away from himself more impressively and completely…?” Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics I/1, The Doctrine of the Word of God, ed. T. F. Torrance and G. W. Bromiley, trans. G. W. Bromiley (T&T Clark, 1975), 117. Cf. Arnold’s earlier engagement with Barth.

5. Arnold was already familiar with Denck from a collection of the latter’s writings published in Arnold’s Quellen book series. See Adolf Metus Schwindt, Hans Denck: Ein Vorkämpfer undogmatischen Christentums 1495–1527 [Hans Denck: A champion of undogmatic Christianity] (Neuwerkverlag, 1923).

6. Evidently, the size of the project and the demands of 1935 played a significant part in delaying the completion of the work. At the beginning of the year, Arnold revealed, “I would like to finish the Inner Land book before I leave for Silum. This work will probably only take about eight days. I had originally intended a lengthy structure for the final chapter, but I want to abandon this for the following reasons: Thomas Müntzer alone took me another four weeks. But that could be published some other time as a monograph. A little book of 150 pages would have to be written: Thomas Müntzer: German Christian? Then I could quickly finish the Inner Land book now. The following problem arises in the final chapter: What is the relationship between the printed word of the Bible and the living word given to us by the Holy Spirit? This is not that easy to express. Thomas Münzer and Schwenckfeld and Sebastian Franck give us the direction for solving this question. Therefore, I have decided to pull the tree in my heart out by its roots and finish Inner Land in the first [available] eight days of quiet.” See meeting transcript, January 4, 1935 (EA 324). Notably, Schwenckfeld appears in place of Denck here, though he is only mentioned in passing in the final edition. The material that Hardy used to complete Inner Land was bound in an unpublished book (EA 33/04); cf. EA 174; EA 505.

7. See e.g., Eberhard Arnold, “Fort vom Kompromiβ und Schatten” [Away from compromise and shadow], Die Wegwarte 10–11 (1925): 105–7 (EA 25/08).