“Soul and Spirit” is the third major chapter of volume one of Inner Land, The Inner Life. Arnold opens this chapter by addressing the problem of death. The First World War saw widespread casualties on all sides, especially among young men; but Arnold believes that suicide, murder, and abortion have all been on the increase as well since the war ended.1 So this topic is of particular relevance. Despite its ubiquity, however, death remains incomprehensible: “Is it not one of the most astonishing facts that death should overcome life?” (63). The problem, Arnold suggests, lies in not grasping the eternal nature of life. “If there is no other future and no other world (which is bound to be victorious because it is the better world), then the injustice that prevails makes nonsense of human existence” (64). Simply in recognizing the absurdity of death, then, people anticipate a fuller life that goes beyond this short existence, even if unknowingly.

This anticipation is confirmed by the Spirit, who gives believers hope for “that which is to come.” In death they dwell within God, and their hope will one day be answered in the resurrection of their bodies to immortal life. Death itself is the result of sin, though even for sin “it is impossible to extinguish the life that God has given us out of his own nature” (67). All die, “yet death is not annihilation” (67). Such is the case even with respect to the Last Judgment – the death visited upon the disobedient will not fully erase their life. Here Arnold devotes space to the consideration of hell and judgment. For him, life in hell is “nothing but the continuation of the lives of those who live for themselves” (69). Those who spent their earthly lives apart from God will spend their eternal lives apart from him too.

The majority of this chapter is given to contemplating the spirit of a person and its relationship to the soul. All natural life lives in God. Human life, however, is different insofar as it derives from God’s own breath (Gen. 2:7). Arnold identifies this breath with the human’s spirit, which is to direct people in all their ways, above soul and body. It also sets us apart from animals, who have only soul and body, and it is the basis for the difference between killing human beings and killing animals; the former is forbidden, the latter, not. Readers should note that since German does not differentiate between proper and common nouns, the word Geist (spirit) is always capitalized, regardless of whether Arnold is referring to the human spirit or the Holy Spirit; and that the orthographic distinction between the two in English, which results in less fluidity, is a product of translation. Nonetheless, Arnold obviously differentiates the two and it is usually clear whether he is referring to the human spirit or the Holy Spirit.2

Despite the lofty role intended for it, the human spirit has turned away from God and often seeks its own ends in honor, self-redemption, and loyalty to blood or class. “God’s rule, however, means that no one seeks his own advantage anymore, that no one seeks privileges for himself anymore, and that self-preservation is nowhere placed above the Spirit’s cause—that of unity” (73). As such, addressing instances in which the human spirit is not aligned with God’s, Arnold writes, “As long as the rulership of God and his kingdom are put in the background, efforts toward human progress of any kind will inevitably break down over and over again” (74). Indeed, even if they do not fail now, they will eventually face judgement. Yet hope remains. Arnold prophesies that “the hour is near when the spirits of people far and wide will be gripped and called by the Spirit of God” (74). Whether this has already taken place in our time or is yet to come is open to interpretation. Apart from concrete particulars, at base this statement represents a hope for Spirit-led renewal throughout the earth.

True humanity is found in the rule of soul and body through the spirit. The soul stands somewhat between spirit and body, the spiritual and the material. Arnold is careful, however. The physical or material itself is “not the real enemy of the soul” (75). It is simply that they have escaped the spirit’s rule, the spirit which was originally intended to govern soul and body alike. Thus, “being filled with what God’s eternal will decrees can never result in alienation from life” (77). Rather, “those who are gripped by God’s Spirit turn to his creation with all the interest that comes from God’s love” (77). He does not mention it, but Arnold’s argument here can be read as an implicit response to Friedrich Nietzsche. Arnold’s doctoral thesis focused on Christian and anti-Christian elements in the works of this philosopher, who criticized Christianity for its abandonment of the earth in favor of an imaginary world beyond. For example Neitche writes: “I entreat you, my brothers, remain true to the earth, and do not believe those who speak to you of superterrestrial hopes! They are poisoners, whether they know it or not.”3 For Arnold, true Christianity does not flee but embraces the earth.

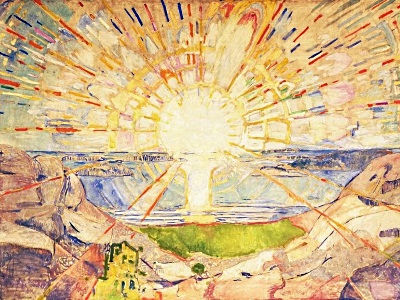

So, the the spirit is to rule soul and body, but in unity with God’s Spirit—and, subsequently, in unity with other human spirits too. Arnold finds Hebrews 4:12 to be an important source in this connection: “The word of God is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword, piercing until it divides soul from spirit.” He takes this division enacted by God’s word quite literally. It allows the person to “recognize without a shadow of doubt the unspiritual sensuality of the unredeemed life of the soul” (78). Without such separation, spirit and soul will be confused, leading to spiritual death, a widespread phenomenon in the various movements that followed the First World War and, generally speaking, in the age-old human pursuit of mammon and possession. The repercussions of this spiritless life of the soul are immense but largely overlooked by those who lead these lives: “We know that if the sun were extinguished it would mean instantaneous death for all life on our planet. We admit that an old riverbed will not have running water anymore once the stream has been diverted” (79).

Arnold proceeds to offer a closer definition of the soul: “The soul embraces all manifestations of life. It is the bearer of everything that is alive in us. The soul is the total consciousness of the individual: the combination of all our sensual perceptions as well as the concentration of all our higher and spiritual relationships” (81). In fact, the soul is effectively synonymous with a person’s life, a fact apparent in older Bible translations that use the two words interchangeably.

The blood also deserves special attention here due to its close connection to the soul. Recalling the war, Arnold points to the unexpected difference between people’s reactions to seeing blood being shed and seeing dead bodies. Generally, “the thought of blood that is shed is more horrifying to us than the thought of the graves of the slain” (82). For Arnold, this is because a person’s soul resides within the blood. Fables in which people sign pacts with their blood reflect the same belief. In both Goethe’s Faust and older versions of the story, for example, Faust uses his own blood to sign a pact in which his soul is at stake. Whether all of this should be taken literally or not is left unsaid. Arnold’s point is simply that the soul’s close connection to the blood makes it susceptible to the latter’s weaknesses, particularly in relation to appeals to blood ties that elevate the needs of one group over other, allegedly inferior groups:4 “An enfeebled soul is swept along whenever the individual or the nation is roused inwardly by an appeal to the blood or by an insistence on blood ties” (83).

The alternative is to be found in the life of the spirit, which persists in death where blood does not. Indeed, the spirit ruled by God’s Spirit is willing even to submit the body to death, letting its blood be shed, for the life to come. In Jesus we belong to “another homeland, different from the land of our blood,” and this “makes us so truly sons and daughters of God that we can represent no other interests save those of his heart and his kingdom” (85). As such, it is not our blood – as in nationalist movements, for instance – but the Holy Spirit that unites us with others.

Approaching the end of the first section of Inner Land, Arnold summarizes his view of human beings and their interconnectedness with the rest of creation. First, on the most basic level, people have a material form, which they share with all earthly things. Second, they are also organic, a feature they share with all living things. Third, they have souls in common with other animals, encompassing the blood and consciousness. Fourth, the first aspect that makes us distinctly human is what Arnold refers to as the heart, which is the seat of emotion, thought, and will. Finally, the core of that which is distinctly human is found in the spirit. It “forms the center that dominates the whole” (92). And it is purposed for a life in unity with the Holy Spirit: “The innermost chamber of our soul must always be filled with the Spirit of Jesus Christ. The chamber where our spirit is enthroned must always be filled with all his thoughts and with his will, that is, with every impulse of his heart” (95).

Continue:

Introduction

1.1. The Inner Life

1.2. The Heart

1.3. Soul and Spirit

2.1. The Conscience and Its Witness

2.2. The Conscience and Its Restoration

3.1. The Experience of God

3.2. The Peace of God

4.1. Light and Fire

4.2. The Holy Spirit

5.1. The Living Word

1. In talking about the swing of murders, Arnold is likely referring to the wave of assassinations and clashes between leftist revolutionaries and right-wing nationalists in this period (and later, assassinations by the Brown Shirts and Nazis), rather than individual non-political homicides. Cf. Inner Land 2:37, 64–65; 3:9. On suicide, Christian Goeschel writes, “After 1918, contemporaries generally believed that times of general uncertainty, political disorder, and socio-economic hardship inevitably led to rising suicide levels. … Generally, contemporary observers not only blamed the defeat of 1918, the inflation and the Versailles Treaty for the increasing suicide levels, but also the impact of modernity and secularization.” Goeschel critically assesses these sentiments using data from the period. See his Suicide in Nazi Germany (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 11–55, on the Weimar Period. Abortion remained illegal in Weimar Germany, though it still took place and was subject to debate by medical professionals, women, and political and religious figures alike. Cornelie Usborne writes of “the enormous variation in national abortion statistics.” “Abortion in Weimar Germany – the Debate amongst the Medical Profession,” Continuity and Change 5, no. 2 (1990): 199–224, at 207.

2. E.g. “For the spirit, the highest destiny is to be infused with divine Spirit, to be united with the Holy Spirit” (93).

3. Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book for Everyone and No One (1885), trans. R. J. Hollingdale (Penguin, 2003), 42.

4. The persecution of Jews under Hitler and earlier is not the focus of Inner Land, though Arnold’s rejection of nationalism here surely extends to Nazi antisemitism. In his “Light and Fire” chapter, he criticises the exclusionary appropriation of the swastika, which “belongs to primeval man. All his descendants, without distinction of race or blood, have a right to it. So it is not surprising that all the Aryan tribes as well as the Phoenicians of Canaan preserved this sign,” including “the Jewish inhabitants of Canaan” (IL 4:24)! See the corresponding article in this series.